In Florence, Alabama, there sits a log cabin, the birthplace and childhood home of William Christopher ("W.C.") Handy, known as the Father of the Blues; today, it serves as a museum and monument. Florence sits in Alabama's 5th Congressional District, which has been a focus of national attention since the soon departed, and never regretted, Congressman Parker Griffith switched to the Republican Party in a "Christmas Surprise" in December 2009. Griffith was bounced by his new party in the June primary, and the general election contest will be between Democrat Steve Raby and Madison County Republican Commissioner Mo Brooks. And now, the 5th District is being subjected to another round of - are we ready? The CONVENTIONAL WISDOM.

If you're like me, after a few decades of working in Alabama Democratic affairs, the phrase "conventional wisdom" engenders a reflexive flinch. Because by now, we know what the Conventional Wisdom is going to be. "The district is white-majority, it's in Alabama. A Democrat can't win it." As George and Ira Gershwin, so clearly influenced by Handy, wrote, "It Ain't Necessarily So." In the case of what is today the 5th District, the last time a Republican won a general election to this seat as such, that Republican was John Benton Callis, and most of the votes were counted by his recent comrades in blue uniforms. (After his one term in Congress, Callis moved back to Wisconsin.)

True to form, inside the Beltway, this district is being referred to as some sort of likely Republican hold. CQ/Roll Call refers to the district as "Leans Republican." What did CQ/Roll Call have to say about the Democratic primary?

That would be the same Taze Shepard who got an impressive 22.7% of the vote, to Raby's 61.7%, in the primary. (I'm not sure to whom CQ/Roll Call was talking. It wasn't me.) The New York Times gives them one-up, calling the seat "Solid Republican." (The Washington Post's politics page simply refers to the seat as "open," without offering a forecast at this time. Interestingly, they do the same thing with the black-majority 7th District, which has exactly zero chance of going Republican. It's interesting how such "labels" make a Republican takeover appear more likely ...) Let's see if we can't help CQ/Roll Call and these other folks get a better handle on the reality on the ground in the 5th.

The numbers. I understand that an understaffed editorial office in Washington has trouble keeping track of 435 Congressional districts, while at the same time trying to follow 100 Senate seats, 50 governorships, the White House, and the occasional embryonic Presidential campaign. But ignoring 140 years of voting history, and important voting metrics, is hard to justify. Part of the problem is faulty methodology. Especially when an incumbent is not in the mix, most of these sources take time to look at one metric, the district's Presidential vote. This in itself is unwise. 83 House districts are currently held by members whose party failed to carry their district in the 2008 Presidential election. A disproportionate number of those 83 members of Congress are Southern Democrats, reflecting a longstanding Southern history of states and districts splitting their ballots, voting Republican in the Presidential election, but Democratic in Congressional and local races.

Slavish devotion to the "Presidential metric" presupposes that someone who votes for one party for President will follow that party down the ballot. While there is strong and well-accepted empirical evidence of a correlation, that does not always hold, especially in non-Presidential years. In the case of the 5th District, a look at downballot voting patterns reveals that it is fundamentally a Democratic district, which happens to vote Republican in most Presidential elections. (And a passing note, the "Southern" Democratic tickets headed by Clinton and Gore from 1992-2000 carried many of the counties in this district.)

If you're like me, after a few decades of working in Alabama Democratic affairs, the phrase "conventional wisdom" engenders a reflexive flinch. Because by now, we know what the Conventional Wisdom is going to be. "The district is white-majority, it's in Alabama. A Democrat can't win it." As George and Ira Gershwin, so clearly influenced by Handy, wrote, "It Ain't Necessarily So." In the case of what is today the 5th District, the last time a Republican won a general election to this seat as such, that Republican was John Benton Callis, and most of the votes were counted by his recent comrades in blue uniforms. (After his one term in Congress, Callis moved back to Wisconsin.)

True to form, inside the Beltway, this district is being referred to as some sort of likely Republican hold. CQ/Roll Call refers to the district as "Leans Republican." What did CQ/Roll Call have to say about the Democratic primary?

The apparent Democratic frontrunner is former Alabama Board of Education member Taze Shepard, an attorney who is the grandson of the late Sen. John Sparkman (D).

That would be the same Taze Shepard who got an impressive 22.7% of the vote, to Raby's 61.7%, in the primary. (I'm not sure to whom CQ/Roll Call was talking. It wasn't me.) The New York Times gives them one-up, calling the seat "Solid Republican." (The Washington Post's politics page simply refers to the seat as "open," without offering a forecast at this time. Interestingly, they do the same thing with the black-majority 7th District, which has exactly zero chance of going Republican. It's interesting how such "labels" make a Republican takeover appear more likely ...) Let's see if we can't help CQ/Roll Call and these other folks get a better handle on the reality on the ground in the 5th.

The numbers. I understand that an understaffed editorial office in Washington has trouble keeping track of 435 Congressional districts, while at the same time trying to follow 100 Senate seats, 50 governorships, the White House, and the occasional embryonic Presidential campaign. But ignoring 140 years of voting history, and important voting metrics, is hard to justify. Part of the problem is faulty methodology. Especially when an incumbent is not in the mix, most of these sources take time to look at one metric, the district's Presidential vote. This in itself is unwise. 83 House districts are currently held by members whose party failed to carry their district in the 2008 Presidential election. A disproportionate number of those 83 members of Congress are Southern Democrats, reflecting a longstanding Southern history of states and districts splitting their ballots, voting Republican in the Presidential election, but Democratic in Congressional and local races.

Slavish devotion to the "Presidential metric" presupposes that someone who votes for one party for President will follow that party down the ballot. While there is strong and well-accepted empirical evidence of a correlation, that does not always hold, especially in non-Presidential years. In the case of the 5th District, a look at downballot voting patterns reveals that it is fundamentally a Democratic district, which happens to vote Republican in most Presidential elections. (And a passing note, the "Southern" Democratic tickets headed by Clinton and Gore from 1992-2000 carried many of the counties in this district.)

If you want to know how folks vote in the 5th District for Representative, you will get a better view if you look to see how they vote for Representative. State Representative in 2006, that is.

| District | Party | Candidate | TOTAL IN 5TH CD |

|---|---|---|---|

| State House 01 | DEM | Irons | 8,410 |

| State House 02 | DEM | Curtis | 7,704 |

| State House 03 | DEM | Black | 9,585 |

| State House 04 | DEM | Mitchell | 5,988 |

| State House 05 | DEM | White | 7,071 |

| State House 06 | DEM | Schmitz† | 7,202 |

| State House 07 | DEM | Letson | 7,680 |

| State House 08 | DEM | Dukes | 7,833 |

| State House 09 | DEM | Grantland | 6,349 |

| State House 18 | DEM | Morrow | 2,357 |

| State House 19 | DEM | Hall, A.* | 10,449 |

| State House 21 | DEM | Hinshaw | 6,063 |

| State House 22 | DEM | Hall, L. | 6,100 |

| State House 23 | DEM | Robinson | 7,969 |

| 100,760 | |||

| TOTAL % D IN 5TH CD | 13 Seats | 59.0% | |

| State House 01 | REP | Smith | 4,511 |

| State House 02 | REP | Pettus | 4,115 |

| State House 04 | REP | Hammon | 8,097 |

| State House 05 | REP | Coffman | 5,277 |

| State House 06 | REP | Stiles | 3,960 |

| State House 07 | REP | Robinson | 2,475 |

| State House 09 | REP | Stone | 4,895 |

| State House 10 | REP | Ball | 9,041 |

| State House 20 | REP | Sanderford | 13,859 |

| State House 21 | REP | Wiggins | 3,861 |

| State House 25 | REP | McCutcheon | 9,983 |

| 70,074 | |||

| TOTAL % R IN 5TH CD | 4 Seats | 41.0% |

* Currently held by Taylor (D) after 2007 special.

† Currently held by Williams (R) after 2009 special.

While the Republicans have taken one seat since the election in which this chart was compiled, that takeaway happened in a special, making it a poor model for altering observations from a cycle more like the one in progress, than like a low-turnout special.

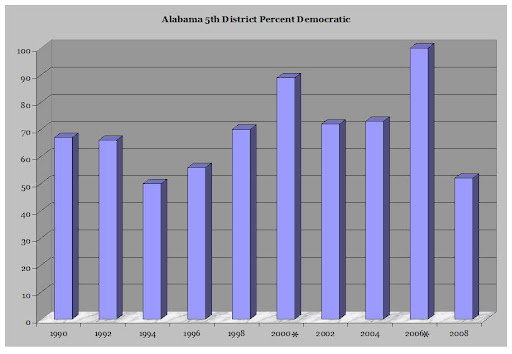

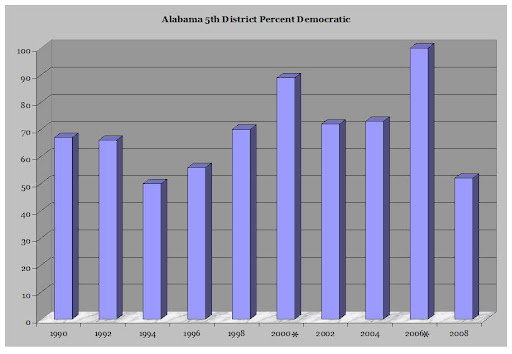

Another metric one might prefer to the Presidential vote, in predicting a Congressional vote is ... the Congressional vote. Let's look at this district since Bud Cramer's first election in 1990, with a couple of points in mind:

* No Republican nominee

* No Republican nominee

Another metric one might prefer to the Presidential vote, in predicting a Congressional vote is ... the Congressional vote. Let's look at this district since Bud Cramer's first election in 1990, with a couple of points in mind:

* No Republican nominee

* No Republican nomineeFirst, is the pure and simple fact that this district has a solid Democratic voting record in Congressional races - an average of 69.5% over nearly two decades! This is even better than the Democratic totals in state legislative races, and remains so even if Cramer's unopposed 2006 re-election is factored out. It's painful to watch knowledgeable people rate such a Democratic district as Republican-leaning.

But a more subtle, and perhaps more important phenomenon revealed by the above chart is the distinction between the Democratic performance in the 5th in presidential and gubernatorial election years. The Democratic nominee in this district gets a boost in gubernatorial years of an average of 4.6%, an effect that is understated by the inclusion of the 1994 gubernatorial cycle in this calculation. (The national Democratic Congressional vote hit record lows that year, a fact that was reflected in the 5th.) So, even if you make a presumption that the 52%-48% Democratic majority from 2008 is some sort of more "current" norm than the modern historical average, that baseline should look more like 56% or 57% Democratic in 2010. Suffice it to say, if you want to find an "objective number" that makes this district look Republican, you have to go looking for the Presidential totals.

A passing word is in order about that 48% GOP showing in 2008. Not only did it take place in a presidential year (remember, that means a ~4.6% GOP swing), that swing was exaggerated by the racial polarization against Obama at the top of the ticket. Statewide exit polling data indicate that Obama got about 10% of the white vote in Alabama, and that was acutely felt in the 5th. Another factor to consider is that the 2008 general election campaign brought out serious dirt on then-Democrat Griffith, including allegations that he had deliberately low-dosed cancer patients to prolong their chemo regimens, to make more money. (Griffith was an oncologist before entering politics.) This charge was the subject of a 3,000+ GRP media buy by the RCCC, and doubtless cost Griffith several points. No one has ever whispered that sort of dirt about Raby. In fact, Taze Shepard, his primary opponent, made a strong effort to go negative on Raby in the primary. The best dirt he could find - and he made it the subject of a TV buy of at least 1,500 GRP, maybe more - was an accusation that Raby - horror! - donated to Republicans! Now, the truth was and is, Raby did so for his lobbying clients, who also need GOP votes on the Hill. But the only real effect of this media blitz was to immunize Raby from any accusation by Brooks that he's a liberal party hack. I am sure Shepard's thank-you card from Raby is in the mail.

The candidates. Raby. The Democratic nominee is Huntsville lobbyist and consultant Steve Raby. This is Raby's first venture on the ballot in his own name, but he is no stranger to the game. He served for years as a top aide to the late Senator Howell Heflin, and doubtless learnt a thing or two from "The Judge" about winning Alabama elections. Most of Raby's business is centered on the sprawling Army/NASA complex at Redstone Arsenal, and among its large contracting community.

This boosts Raby in two ways. First, his clear ties to the defense industry immunize him from the inevitable canned ads calling him a "Pelosi Liberal." Secondly, it gives him a superior entree to the substantial contributions those contractors always bestow. Both Raby's fundraising savvy, and the belief of those local contractors that Raby is the favorite, are evidenced by the fact that Raby was one of only four Democratic challengers nationally to outraise a Republican incumbent in the first quarter. (This is especially impressive if you consider the RCCC/leadership largess that was being lavished on Griffith in an effort to save his seat.) Raby grew up in cotton farming country outside Huntsville, and despite his time in D.C. and around Huntsville's rocket scientists, he retains a folksy manner and direct speech that go over well in the rural areas on the district's eastern and western ends. Raby is a multi-generational native of the district, and in the parts of this district that aren't NASA-dominated, that is an important consideration. From his long career with Heflin, Raby can tell you anecdotes at the drop of a hat, about places in the district with names like Town Creek, Center Star, Skyline Mountain and Capshaw, that would leave Brooks fumbling over his map and note cards.

This boosts Raby in two ways. First, his clear ties to the defense industry immunize him from the inevitable canned ads calling him a "Pelosi Liberal." Secondly, it gives him a superior entree to the substantial contributions those contractors always bestow. Both Raby's fundraising savvy, and the belief of those local contractors that Raby is the favorite, are evidenced by the fact that Raby was one of only four Democratic challengers nationally to outraise a Republican incumbent in the first quarter. (This is especially impressive if you consider the RCCC/leadership largess that was being lavished on Griffith in an effort to save his seat.) Raby grew up in cotton farming country outside Huntsville, and despite his time in D.C. and around Huntsville's rocket scientists, he retains a folksy manner and direct speech that go over well in the rural areas on the district's eastern and western ends. Raby is a multi-generational native of the district, and in the parts of this district that aren't NASA-dominated, that is an important consideration. From his long career with Heflin, Raby can tell you anecdotes at the drop of a hat, about places in the district with names like Town Creek, Center Star, Skyline Mountain and Capshaw, that would leave Brooks fumbling over his map and note cards.

Brooks. The Republicans have fielded Mo Brooks, who at first looks to have a modestly successful political record. However, at closer look, his several elections to the Alabama House, and to the Madison County Commission, have all been in districts that were carefully drawn to be safe Republican districts. More precisely, districts drawn to suck as many Republican votes as possible out of swing districts. His wins in contested primaries there show little more than his acceptability to reliable Republican voters. The one time Brooks has been on a countywide general election ballot in Madison County, after he was appointed district attorney by then-Governor Guy Hunt, he lost badly to Democrat Tim Morgan, 54%-46% - and Madison County is historically the strongest Republican region in the district. Before his win over Griffith, the last time Brooks was on the GOP primary ballot across the district was for his unsuccessful 2006 run for the Republican nomination for Lieutenant Governor. Despite the fact he was the "local" candidate (his two opponents were from 90 and 180 miles away), the "Friends and Neighbors" vote only got Brooks 49% of the vote in the counties in the 5th District. (That such a lukewarm primary candidate could trounce Griffith so badly in the GOP primary should be an object lesson for any would-be party switchers, anywhere.)

Brooks. The Republicans have fielded Mo Brooks, who at first looks to have a modestly successful political record. However, at closer look, his several elections to the Alabama House, and to the Madison County Commission, have all been in districts that were carefully drawn to be safe Republican districts. More precisely, districts drawn to suck as many Republican votes as possible out of swing districts. His wins in contested primaries there show little more than his acceptability to reliable Republican voters. The one time Brooks has been on a countywide general election ballot in Madison County, after he was appointed district attorney by then-Governor Guy Hunt, he lost badly to Democrat Tim Morgan, 54%-46% - and Madison County is historically the strongest Republican region in the district. Before his win over Griffith, the last time Brooks was on the GOP primary ballot across the district was for his unsuccessful 2006 run for the Republican nomination for Lieutenant Governor. Despite the fact he was the "local" candidate (his two opponents were from 90 and 180 miles away), the "Friends and Neighbors" vote only got Brooks 49% of the vote in the counties in the 5th District. (That such a lukewarm primary candidate could trounce Griffith so badly in the GOP primary should be an object lesson for any would-be party switchers, anywhere.)

Brooks is no Ronald Reagan behind the lectern, but he does reliably, if dryly, recite the mandatory GOP line about abortion, guns, and taxes. However, in a district where the largest employer by far is the Federal government, there is a lot of sentiment for not cutting taxes too far. More problematic for Brooks is his somewhat offputting affect, which may have explained his 2006 showing. Like many alumni of Duke - of which Brooks is one - he leaves you with the distinct impression that he wants you to know that, as much better than your school as Duke is, he could have gotten in someplace even more selective had he wanted. (I already know from whom I will get the hate mail on that one.) If Brooks is to have a chance to win, he will have to make substantial inroads in - or carry - the bedrock Democratic counties on the eastern and western ends of the district. In the blue-collar towns and farmlands of those counties, aloof doesn't sell well.

Other factors. Of course, the national media line is that this is going to be a bad, bad year for Democrats. To be sure, there is some truth to that, even if the repetition of the mantra is not always borne out by facts in the real world. Special election wins by Democrats in places like the Pennsylvania 12th this year, and New York 23rd last December, keep stepping on that story line. Of course national trends will be felt here, but the terrain on which they will play out - as shown above - is much more Democratic than thought inside the Beltway.

An interesting piece caught my eye in The New York Times last week, and I instantly thought of the 5th. Citing some fairly solid statistical evidence, it stated that the anti-incumbent-President effect is less in districts where the economy is doing better, and more in places it is worse. It posited that many of the battleground districts (among which it isn't yet counting the 5th) are faring better economically than the nation as a whole, which may result in unexpected good news for Democrats in November. Add the 5th to those economic high-performers. The 2005 Defense Base Re-Alignment and Closure (BRAC) process resulted in a net inflow into Redstone Arsenal of 4,700 jobs, not counting the associated jobs with outside contractors and suppliers, families, and the "multiplier effect." Huntsville even had to open a special website for workers moving in. Those newly-employed people are only arriving in numbers this year, and local business is feeling the benefits. Houses are being built, restaurants are opening and hiring, and schools are hiring teachers. The unemployment rate in Madison County was only 7.5% and dropping in May, well below the state average of 10.5%. When Brooks tries to work the local meat-and-three cafe with talk of the bad economy, he's apt to be greeted with the excuse that his listener has to be on time to her new job.

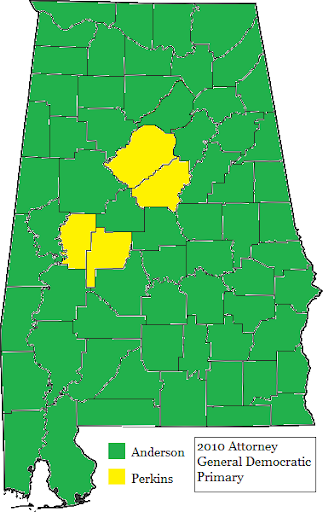

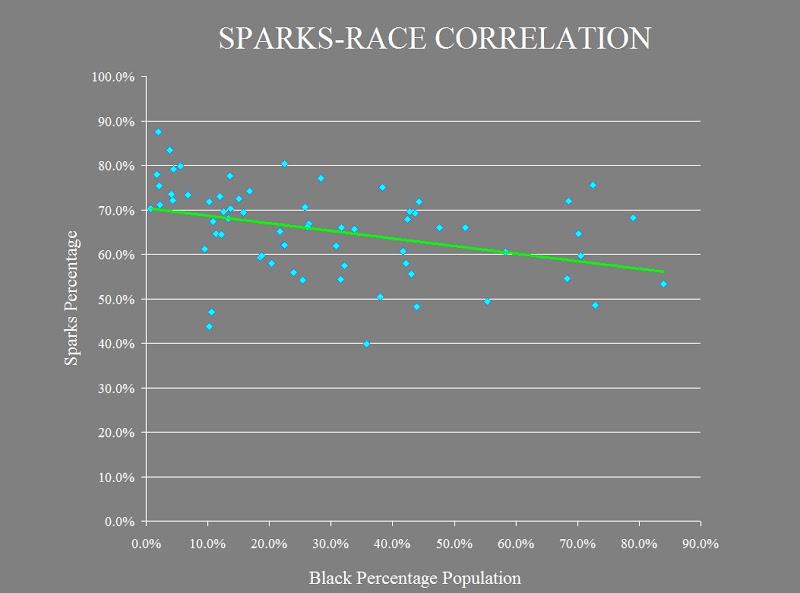

One other factor that I have talked about elsewhere is the top of the Democratic ticket. Raby took two wins on primary day - his race and the gubernatorial primary. He will not be dealing with the prospect of Artur Davis polarizing the electorate along racial lines (see, Obama, 10%, supra), and the head of his ticket will be Ag Commissioner Ron Sparks - whose Fort Payne home is a mere 15 miles outside the district. The Tennessee Valley has not had a native son in the Governor's Mansion since 1971, and Sparks's nomination is apt to have a lot of the Democratic base here excited. This should have an especially strong turnout impact in Jackson County, the Democratic stronghold that adjoins Sparks's native DeKalb. (The GOP gubernatorial nominee will be from either 130 miles (Bentley) or 360 miles (Byrne) away from Huntsville.) As I have noted elsewhere, solid empirical evidence has demonstrated that the "Friends and Neighbors" vote first identified by V.O. Key continues to have effects in the South, even on candidates downballot from the "neighbor." These anecdotal factors indicate that the historical 4.6% gubernatorial-year Democratic boost in this district should be even greater, given this lineup.

Gambling, as everyone in Alabama has been told by now, is a uniquely Democratic Party sin. Pray that you can resist its temptation. But if you must yield, whatever you do, don't bet on the Alabama 5th going Republican this November.

But a more subtle, and perhaps more important phenomenon revealed by the above chart is the distinction between the Democratic performance in the 5th in presidential and gubernatorial election years. The Democratic nominee in this district gets a boost in gubernatorial years of an average of 4.6%, an effect that is understated by the inclusion of the 1994 gubernatorial cycle in this calculation. (The national Democratic Congressional vote hit record lows that year, a fact that was reflected in the 5th.) So, even if you make a presumption that the 52%-48% Democratic majority from 2008 is some sort of more "current" norm than the modern historical average, that baseline should look more like 56% or 57% Democratic in 2010. Suffice it to say, if you want to find an "objective number" that makes this district look Republican, you have to go looking for the Presidential totals.

A passing word is in order about that 48% GOP showing in 2008. Not only did it take place in a presidential year (remember, that means a ~4.6% GOP swing), that swing was exaggerated by the racial polarization against Obama at the top of the ticket. Statewide exit polling data indicate that Obama got about 10% of the white vote in Alabama, and that was acutely felt in the 5th. Another factor to consider is that the 2008 general election campaign brought out serious dirt on then-Democrat Griffith, including allegations that he had deliberately low-dosed cancer patients to prolong their chemo regimens, to make more money. (Griffith was an oncologist before entering politics.) This charge was the subject of a 3,000+ GRP media buy by the RCCC, and doubtless cost Griffith several points. No one has ever whispered that sort of dirt about Raby. In fact, Taze Shepard, his primary opponent, made a strong effort to go negative on Raby in the primary. The best dirt he could find - and he made it the subject of a TV buy of at least 1,500 GRP, maybe more - was an accusation that Raby - horror! - donated to Republicans! Now, the truth was and is, Raby did so for his lobbying clients, who also need GOP votes on the Hill. But the only real effect of this media blitz was to immunize Raby from any accusation by Brooks that he's a liberal party hack. I am sure Shepard's thank-you card from Raby is in the mail.

The candidates. Raby. The Democratic nominee is Huntsville lobbyist and consultant Steve Raby. This is Raby's first venture on the ballot in his own name, but he is no stranger to the game. He served for years as a top aide to the late Senator Howell Heflin, and doubtless learnt a thing or two from "The Judge" about winning Alabama elections. Most of Raby's business is centered on the sprawling Army/NASA complex at Redstone Arsenal, and among its large contracting community.

This boosts Raby in two ways. First, his clear ties to the defense industry immunize him from the inevitable canned ads calling him a "Pelosi Liberal." Secondly, it gives him a superior entree to the substantial contributions those contractors always bestow. Both Raby's fundraising savvy, and the belief of those local contractors that Raby is the favorite, are evidenced by the fact that Raby was one of only four Democratic challengers nationally to outraise a Republican incumbent in the first quarter. (This is especially impressive if you consider the RCCC/leadership largess that was being lavished on Griffith in an effort to save his seat.) Raby grew up in cotton farming country outside Huntsville, and despite his time in D.C. and around Huntsville's rocket scientists, he retains a folksy manner and direct speech that go over well in the rural areas on the district's eastern and western ends. Raby is a multi-generational native of the district, and in the parts of this district that aren't NASA-dominated, that is an important consideration. From his long career with Heflin, Raby can tell you anecdotes at the drop of a hat, about places in the district with names like Town Creek, Center Star, Skyline Mountain and Capshaw, that would leave Brooks fumbling over his map and note cards.

This boosts Raby in two ways. First, his clear ties to the defense industry immunize him from the inevitable canned ads calling him a "Pelosi Liberal." Secondly, it gives him a superior entree to the substantial contributions those contractors always bestow. Both Raby's fundraising savvy, and the belief of those local contractors that Raby is the favorite, are evidenced by the fact that Raby was one of only four Democratic challengers nationally to outraise a Republican incumbent in the first quarter. (This is especially impressive if you consider the RCCC/leadership largess that was being lavished on Griffith in an effort to save his seat.) Raby grew up in cotton farming country outside Huntsville, and despite his time in D.C. and around Huntsville's rocket scientists, he retains a folksy manner and direct speech that go over well in the rural areas on the district's eastern and western ends. Raby is a multi-generational native of the district, and in the parts of this district that aren't NASA-dominated, that is an important consideration. From his long career with Heflin, Raby can tell you anecdotes at the drop of a hat, about places in the district with names like Town Creek, Center Star, Skyline Mountain and Capshaw, that would leave Brooks fumbling over his map and note cards. Brooks. The Republicans have fielded Mo Brooks, who at first looks to have a modestly successful political record. However, at closer look, his several elections to the Alabama House, and to the Madison County Commission, have all been in districts that were carefully drawn to be safe Republican districts. More precisely, districts drawn to suck as many Republican votes as possible out of swing districts. His wins in contested primaries there show little more than his acceptability to reliable Republican voters. The one time Brooks has been on a countywide general election ballot in Madison County, after he was appointed district attorney by then-Governor Guy Hunt, he lost badly to Democrat Tim Morgan, 54%-46% - and Madison County is historically the strongest Republican region in the district. Before his win over Griffith, the last time Brooks was on the GOP primary ballot across the district was for his unsuccessful 2006 run for the Republican nomination for Lieutenant Governor. Despite the fact he was the "local" candidate (his two opponents were from 90 and 180 miles away), the "Friends and Neighbors" vote only got Brooks 49% of the vote in the counties in the 5th District. (That such a lukewarm primary candidate could trounce Griffith so badly in the GOP primary should be an object lesson for any would-be party switchers, anywhere.)

Brooks. The Republicans have fielded Mo Brooks, who at first looks to have a modestly successful political record. However, at closer look, his several elections to the Alabama House, and to the Madison County Commission, have all been in districts that were carefully drawn to be safe Republican districts. More precisely, districts drawn to suck as many Republican votes as possible out of swing districts. His wins in contested primaries there show little more than his acceptability to reliable Republican voters. The one time Brooks has been on a countywide general election ballot in Madison County, after he was appointed district attorney by then-Governor Guy Hunt, he lost badly to Democrat Tim Morgan, 54%-46% - and Madison County is historically the strongest Republican region in the district. Before his win over Griffith, the last time Brooks was on the GOP primary ballot across the district was for his unsuccessful 2006 run for the Republican nomination for Lieutenant Governor. Despite the fact he was the "local" candidate (his two opponents were from 90 and 180 miles away), the "Friends and Neighbors" vote only got Brooks 49% of the vote in the counties in the 5th District. (That such a lukewarm primary candidate could trounce Griffith so badly in the GOP primary should be an object lesson for any would-be party switchers, anywhere.)Brooks is no Ronald Reagan behind the lectern, but he does reliably, if dryly, recite the mandatory GOP line about abortion, guns, and taxes. However, in a district where the largest employer by far is the Federal government, there is a lot of sentiment for not cutting taxes too far. More problematic for Brooks is his somewhat offputting affect, which may have explained his 2006 showing. Like many alumni of Duke - of which Brooks is one - he leaves you with the distinct impression that he wants you to know that, as much better than your school as Duke is, he could have gotten in someplace even more selective had he wanted. (I already know from whom I will get the hate mail on that one.) If Brooks is to have a chance to win, he will have to make substantial inroads in - or carry - the bedrock Democratic counties on the eastern and western ends of the district. In the blue-collar towns and farmlands of those counties, aloof doesn't sell well.

Other factors. Of course, the national media line is that this is going to be a bad, bad year for Democrats. To be sure, there is some truth to that, even if the repetition of the mantra is not always borne out by facts in the real world. Special election wins by Democrats in places like the Pennsylvania 12th this year, and New York 23rd last December, keep stepping on that story line. Of course national trends will be felt here, but the terrain on which they will play out - as shown above - is much more Democratic than thought inside the Beltway.

An interesting piece caught my eye in The New York Times last week, and I instantly thought of the 5th. Citing some fairly solid statistical evidence, it stated that the anti-incumbent-President effect is less in districts where the economy is doing better, and more in places it is worse. It posited that many of the battleground districts (among which it isn't yet counting the 5th) are faring better economically than the nation as a whole, which may result in unexpected good news for Democrats in November. Add the 5th to those economic high-performers. The 2005 Defense Base Re-Alignment and Closure (BRAC) process resulted in a net inflow into Redstone Arsenal of 4,700 jobs, not counting the associated jobs with outside contractors and suppliers, families, and the "multiplier effect." Huntsville even had to open a special website for workers moving in. Those newly-employed people are only arriving in numbers this year, and local business is feeling the benefits. Houses are being built, restaurants are opening and hiring, and schools are hiring teachers. The unemployment rate in Madison County was only 7.5% and dropping in May, well below the state average of 10.5%. When Brooks tries to work the local meat-and-three cafe with talk of the bad economy, he's apt to be greeted with the excuse that his listener has to be on time to her new job.

One other factor that I have talked about elsewhere is the top of the Democratic ticket. Raby took two wins on primary day - his race and the gubernatorial primary. He will not be dealing with the prospect of Artur Davis polarizing the electorate along racial lines (see, Obama, 10%, supra), and the head of his ticket will be Ag Commissioner Ron Sparks - whose Fort Payne home is a mere 15 miles outside the district. The Tennessee Valley has not had a native son in the Governor's Mansion since 1971, and Sparks's nomination is apt to have a lot of the Democratic base here excited. This should have an especially strong turnout impact in Jackson County, the Democratic stronghold that adjoins Sparks's native DeKalb. (The GOP gubernatorial nominee will be from either 130 miles (Bentley) or 360 miles (Byrne) away from Huntsville.) As I have noted elsewhere, solid empirical evidence has demonstrated that the "Friends and Neighbors" vote first identified by V.O. Key continues to have effects in the South, even on candidates downballot from the "neighbor." These anecdotal factors indicate that the historical 4.6% gubernatorial-year Democratic boost in this district should be even greater, given this lineup.

Gambling, as everyone in Alabama has been told by now, is a uniquely Democratic Party sin. Pray that you can resist its temptation. But if you must yield, whatever you do, don't bet on the Alabama 5th going Republican this November.